WHAT’S THE STORY BEHIND GARDEN CITIES?

The world of planning means we come across all sorts of weird and wonderful terminology and concepts. Leaning about these is always fun – so we thought we’d share some interesting insights we’ve gathered in our travels at UPco. First cab off the rank: Garden Cities.

Let’s start with the obvious question… what is a Garden City?

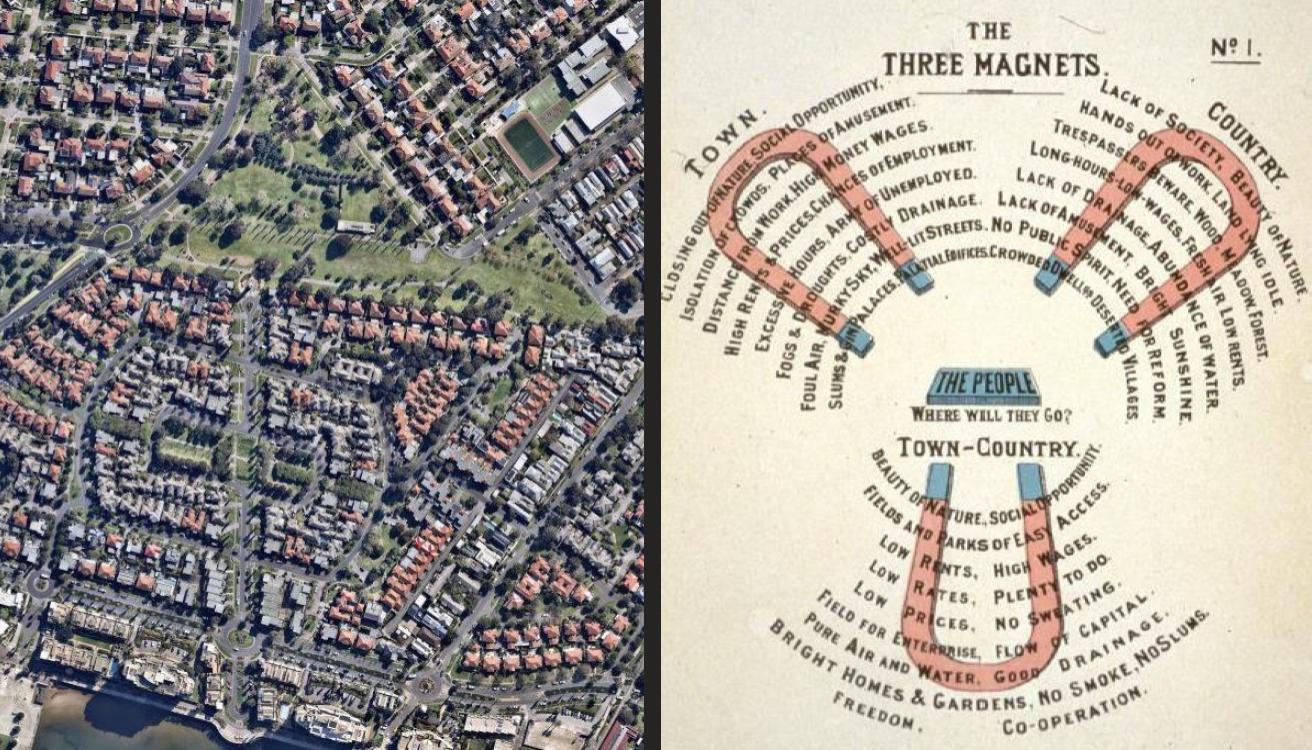

The basic concept of the Garden City is a planned residential community that combines the convenience of urban life with ready access to nature. The concept dates back to 1898, when Ebenezer Howard first came up with the idea as a solution to overcrowding and congestion in cities (which had become a problem after the Industrial Revolution). Funnily enough, Howard wasn’t an architect or planner, but a social reformist – which really shows the important role planning has in solving social issues.

Howard’s scheme involved buying a 6,000-acre patch of ring-fenced agricultural land. On that site, a compact town would be developed, surrounded by a wide green belt, with a civic and cultural complex in the middle (home to things like a city hall, concert hall, theatre and hospital). In concentric circles around this centre would be a park, shopping centre, residential area, and at the outer edge, industry. Ideally, there’d be no more than 32,000 residents.

In Howard’s words, a Garden City was intended to be a ‘joyous union’ of town and country, from which ‘will spring a new hope, new life, new civilisation’. A little idealistic, perhaps, but an appealing ad campaign nonetheless!

Where was the first Garden City built?

Having formed the Garden City Movement to promote his ideas, Ebenezer Howard had the satisfaction of seeing the first Garden City built in Letchworth, about 30 miles from London. It attracted both middle class utopian idealists, and factories relocating from towns (and bringing their workers with them). It’s an interesting combination – and a reminder that, in spite of the genteel-sounding name, a Garden City is meant to be a working town. Happily for Howard, the town was a success – such a success that the concept has been replicated ever since.

In the inter-war period, Howard’s principles were brought to life on our doorstep, with the aptly-named Garden City estate in Port Phillip Bay. Developed at a time when town planning was still in its infancy, Garden City was laid out in a formal fashion with a central boulevard, open reserves and semi-detached two-storey housing that mimicked the type of housing popping up in Britain.

UPco’s own Phil Borelli was actually involved in the revitalisation of Garden City during the 1990s, when Mirvac and the Victorian Government teamed up to develop the adjacent ‘Beacon Cove’ – a residential community that won many awards, and has remained a coveted pocket of the city.

Some say that Howard’s contribution via the Garden City Movement has never received the credit it was due – and we tend to agree. Not only did his concept inspire the collection of original Garden Cities, it influenced housing in some way in almost every country, including America, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa, as well as Europe. And as our cities continue to become more dense, tackling liveability is more important than ever.

Does the concept hold up today?

It depends on who you ask! We sought the opinion of Phil Borelli, because who better to consult than an expert who’s had first-hand experience?

“The original concept that Ebenezer Howard developed holds up, but it’s evolved over time,” mused Phil. “Howard’s concept was intended to address urban problems that plagued British cities and towns following the industrial revolution, like lack of sewerage and drainage, excessive pollution generated by factories, and a lack of open space within urban areas.

“Here in Australia, our cities and towns typify the principles that Howard aspired to – so much so that we tend to take it for granted. In Melbourne, for example, our strategic urban framework is based on activity centres, residential neighbourhoods, industrial and business precincts and generous areas of public open space. It diverges from Howard’s version of the ‘ideal city’ in that it facilitates growth with its surrounding open space – the so-called lungs of the city – being in the form of green wedges rather than a green belt. Growth corridors lie between the green wedges, allowing urban expansion along these corridors. Our smaller cities and towns are planned along similar principles, with public open space being a key feature, although, not typically in the form of a circular belt as Letchworth enjoyed.

“The challenge for planners, nowadays, is to work within environmental constraints, such as the risk of areas being affected by floods, bushfire, landslips and so on; or constrained by other factors like significant vegetation or indigenous cultural heritage. Attributes for development are also important, of course, including the relative costs of providing services to various locations, proximity to places of employment, community facilities and transport.

“While I believe that Howard’s Garden City concept was an important step forward in town planning at that time, I wonder whether he foresaw the issues that increasing population pressure and consequent environmental damage would bring. Would he have adapted his garden city model if he knew? Ultimately, a more flexible approach to urban design and development is needed these days… as this not only allows us to deliver places where people can live and work; it means we can respond better to climate change, population growth and the fragility of the environment.”

We’d love to hear any thoughts you have on Garden Cities. Drop us a line at www.upco.com.au/contact or comment below.